The real estate sector has yet to explore fully the development potential for data centres 10 min read

Driven by the increasing use of cloud computing and generative AI, global investment in data centres reached $36 billion last year (with $22 billion invested in the first five months of 2024 alone).

The demand for hyperscale facilities is surging alongside the demand for traditional cloud services, with the Asia-Pacific projected to see approximately 80% growth in this area by 2028. While many major technology players have announced multibillion-dollar expansions in the Asia-Pacific – to tap into the large end-user market – escalating geopolitical tensions in the region have led data centre operators to consider sovereign and other geopolitical risks in deciding their location.

Australia's strategic position within the Asia-Pacific region, combined with its relatively stable government, presents ideal conditions for investors and developers in this market.

In this Insight, we explore the untapped opportunity to service the ever-increasing demand for data centres, and how developers can capitalise on this.

Key takeaways

- The real estate sector could be capitalising on data centre growth opportunities much more than it is currently, and positioning itself to support the expansion of local and global investor interest in Australian data centres.

- The fundamentals underpinning data centre development do have crossover with other real estate asset classes (ie location, capital partnering strategies and the need to secure regulatory approvals), but data centre development also has unique complexities relating to operating models, the energy transition and structuring.

- Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) is taking an interest in data centres commensurately with the infrastructure's national importance.

- We see three main development models for developers to explore when pursuing data centre opportunities – each with its own challenges.

Industry updates

- In the Asia-Pacific, Keppel DC REIT has over A$7 billion in established data centre assets across 32 facilities (all of which are in the Asia-Pacific region and Europe), and a further A$3.2 billion in its development pipeline.

- Major tech players have also announced multibillion-dollar expansions in the Asia-Pacific region, including AWS's A$13 billion, and Microsoft's A$5 billion, invested in projects in Australia.

- CDC has just announced a plan to build a 500-megawatt $1.4 billion site in Western Sydney.

- Blackstone (an early mover in previous industrial trends) last year announced a partnership with Digital Realty to invest over A$10 billion into data centre projects.

- Macquarie-owned data centre giant AirTrunk is also considering bids (with it rumoured to be valued at over A$15billion).

- It is reported that the value of the global cloud computing market will surge to more than four times its current value (from approximately US$546 billion to US$2.32 trillion).

Development model overview: 'build and operate', 'powered shell' or 'build to spec'

Developers can explore three particular models to pursue data centre opportunities, and each will dictate how the development is funded, constructed and tenanted.

With this model, developers build and then run the data centre themselves. They obtain the property interests, arrange the construction of the data centre, and are responsible for the computer hardware and for the data centre's ongoing operation.

This is where developers build the basic structure of the data centre (the physical building, including cooling and electricity supply, to the specifications of an operator) but not the IT infrastructure inside. The developer then grants a long-term lease/licence to the capacity within that data centre (which may involve co-location and multiple occupiers). Key considerations with this option include:

- appointing specialist consultants and contractors for construction, mechanical and electrical installations;

- structuring tenancy documents appropriately (ie how rent and other consumables should be charged, as well as the breadth of services that the landlord provides);

- income stability from the property, and other sector-specific lender considerations; and

- how the use of the property interplays with the legislative framework relating to critical infrastructure.

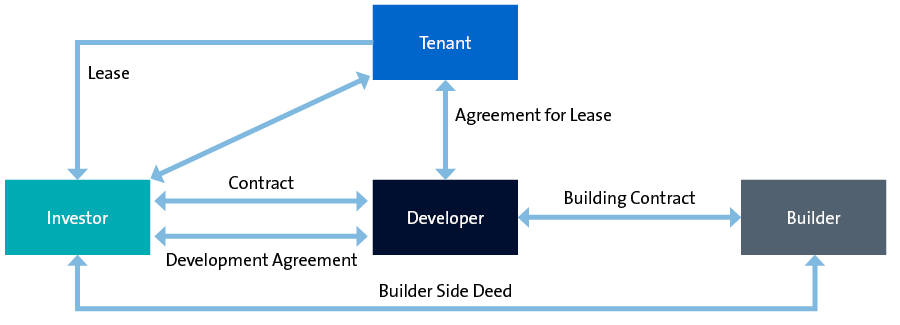

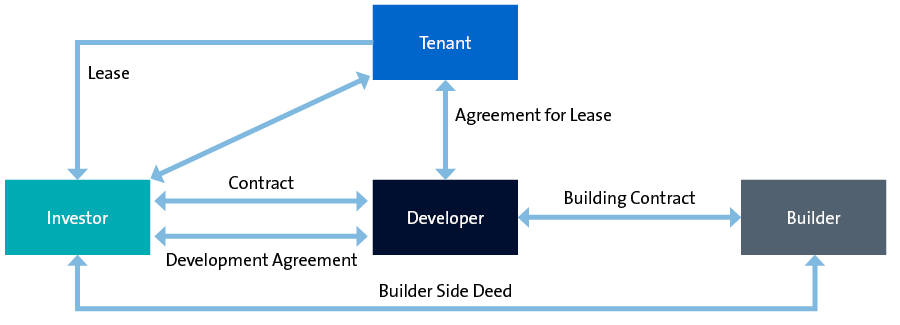

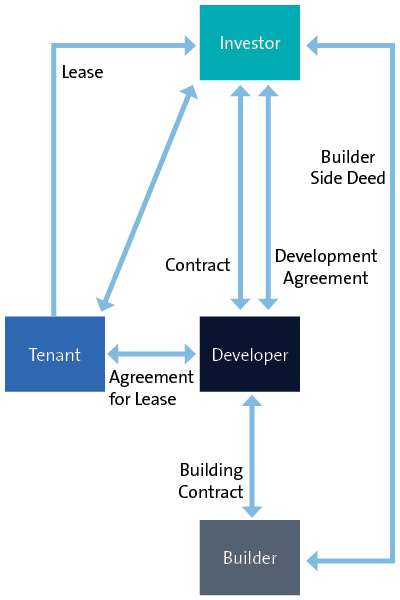

An example of a typical data centre fund-through model, showing the interaction between the capital investors, the developer, builder and tenant, is set out below.

This pathway involves developers building a data centre according to generally acceptable specifications, for hyperscale operators to run once the development is completed. Alternatively, a developer could contract with the hyperscale operator upfront and construct a data centre to the operator's required specifications. In both of these scenarios, the developer typically takes the development risk (although we are aware of the use of 'cost-plus' models, or variations of this).

Location and the AI impact

Selecting the location of a data centre largely depends on planning considerations and the centre's intended use once operational. In all cases, easy access to power generation, transmission and cooling infrastructure is vital – as is keeping delays in data transfer (latency) to a minimum. Location affects the price and investment model (as well as the interplay with the legal framework of a development), so should be considered at an early stage.

Edge data centres typically handle cloud-based tasks. It is important for these data centres to be as close as possible to the users they serve, in order to ensure that data transfers quickly. In Australia, edge data centres are usually located in large cities and towns (close to population centres). Overseas, you might find them on vacant floors of office towers, so as to be close to areas of maximum density. This approach could be appealing to owners of sub-prime office or metropolitan real estate that is not fully tenanted.

However, as land values rise, and industrial properties and brownfield developments become more popular, there has been a shift towards locating AI-focused 'hyperscale' data centres on greenfield sites. These next-generation data centres require physical scale to host processing units in close proximity to each other, which reduces latency within the data centre itself.

Planning and permission requirements

At a high level, data centres may require planning approval for development, use and other related matters, such as native vegetation removal.

These steps vary, depending on which state or territory you're in, but Victoria and New South Wales offer fast-tracked processes for data centres that meet certain thresholds. In Victoria, this is known as the 'Development Facilitation Program'; while in New South Wales, it is the 'State Significant Development' planning pathway.

Depending upon the scale of the data centre and its proposed location, the project's environmental effects may also require assessment. At a national level, projects and other activities ('actions') that will have (or are likely to have) significant impacts on matters of national environmental significance require referral, assessment and approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

Additionally, states and territories may have their own processes for assessing activities with potentially significant environment effects: eg the environment effects statement process under the Environment Effects Act 1978 (Vic). Lastly, if the development site is culturally sensitive or significant, it may require additional approvals before construction can commence.

Understanding the relevant planning framework will be essential in successfully selecting the location for a data centre development.

Tenancy and income structure

Asset-light models, where development and construction are funded by third-party capital, offer flexibility but are burdened by complex stakeholder relationships. In contrast, asset-heavy models, where entities own and manage their data centre assets (eg Blackstone and Equinix) provide more control but involve higher capital expenditure.

Hyperscale data centres are typically occupied via service agreements and occupational licences (sometimes structured as registered leases; but in Australia, more typically, as contractual licences).

User charges are generally structured as three key elements:

- a base charge – based on the capacity of the data centre occupied by the tenant (usually measured on a kilowatt basis) and typically a fixed price with annual increases;

- a power consumption charge – usually charged on a pass-through basis (including accounting for market fluctuations); and

- service charges – variable fees charged on a consumption basis, depending on what level of service and facilitation is provided to the tenant (ie networking, connectivity, hardware, maintenance, technical support, manned security, fire suppression and detection systems, climate / humidity control).

A 'service credit' regime will often overlay the base charges, which are enlivened and accrue if the service levels do not meet the pre-agreed levels. Service levels will often measure response times for critical service-level interruptions (eg in relation to power, cooling or humidity).

These factors should be addressed in the tenancy documents and customer contracts.

ESG and energy

Developers will be under increasing pressure to ensure data centres are powered from renewable energy sources. For example, it is reported that data centres in Singapore account for over 7% of the entire island's energy consumption, prompting public and governmental scrutiny, and the imposition of a development moratorium (which has since been lifted). It is not unusual for AI data centres to use millions of litres of water per day for cooling.

So, while data centres are a key component for city and industry growth, they are energy intensive to operate. Bearing this in mind, investors and developers should consider how the operation of a data centre aligns to any relevant ESG policy frameworks and strategy (including consistency with any decarbonisation, or other ESG, commitments and targets).

Other evolving ways to meet sustainability challenges are:

- sourcing energy from renewable power sources, or offsetting to achieve carbon certification;

- considering higher density, which allows for cooling efficiencies;

- recovering heat waste and redirecting it for other uses;

- co-locating data centres with renewable energy sources (such as wind, battery or solar), and at least partly reducing energy consumption or feeding back into the grid; and

- adopting circular economy principles in operations.

Given that data centres are essentially the 'engine room' of the internet, they require a large, consistent and reliable supply of power to deliver services, respond to demand and maintain system integrity. These energy demands are becoming more pronounced, as cloud computing and AI become increasingly ubiquitous. Recent widespread outages affecting software and telecommunications providers highlight Australia's dependence on these digital essentials. Business (and the public more broadly) is unlikely to accept frequent or extended disruptions.

However, things become more challenging in light of the energy transition. The shift to renewable energy sources brings with it intermittent generation of power, rather than baseload forms of energy, which are available around the clock. As traditional generation capacity is replaced by renewable infrastructure that is 'firmed' up by batteries or energy storage solutions, there may be a mismatch between the energy needs of data centres (which typically require the traditional 'baseload' sources to operate reliably) and what renewable energy sources can offer. To be successful, projects will need to strike a balance: ie negotiate offtake agreements with generators that ensure a stable power supply while also minimising carbon-intensive sources of power.

FIRB and national security businesses

FIRB is taking an interest in data centres commensurately with the infrastructure's national importance.

Its approval will be required at a lower threshold – A$71 million for the 2024 calendar year – for a foreign person to acquire developed commercial land, if the land is or will be fitted out for a business of providing storage of bulk data (such as a data centre). A foreign person that is also a foreign government investor will require FIRB approval to acquire any type of Australian land, irrespective of purchase price.

A foreign person that owns land on which a data centre is situated, or is to be constructed, might need separate FIRB approval in order to start a 'national security business'. Such a landowner will be taken to be starting a national security business if the data centre is used by the operator (usually a tenant) to store 'business critical data' for the Federal Government, for a state or territory government, or for an entity that operates a critical infrastructure asset.

In addition, if the data centre operator is a foreign person, the operator itself might need FIRB approval to start a national security business and/or to acquire a leasehold interest in the land on which the data centre is situated.

Financing considerations

Data centres are a capital-intensive asset and there is no 'one-size-fits-all' approach to financing data centres. While traditional data centres often relied on long-term leases with established cloud service providers to deliver a stable and predictable revenue stream, we are witnessing an evolution in the way customers are contracting with data centre capacity. The result is fewer long-term lease arrangements (potentially accentuated by an increasing shift to AI data centres), combined with a move to shorter-term contracts with different counterparties of varying credit quality.

Developers may look to finance data centres through a number of different methods, depending on what works for their particular data centre (or centres), including:

- 'core-plus' infrastructure-style financing;

- corporate or leveraged-style financing solutions;

- portfolio financing across a number of data centres; or

- asset-backed securitisation.

Traditional project finance lenders can provide finance to data centres as long as the parameters are right. These lenders will be looking for hallmarks of traditional infrastructure assets, such as clarity around land tenure and (critically) long-term lease/offtake arrangements backed by creditworthy counterparties. In seeking this style of financing, developers will need to factor in the broader levels of control associated with core-plus infrastructure financing, including detailed lender diligence regarding (and consent rights over) the contract suite, as well as a requirement for step-in rights to cure any contractual breaches by the owner. This style of financing may be more appropriate for greenfield projects, which are underpinned by long-term lease/offtake arrangements.

A number of developers continue to fund data centres through their general corporate facilities, based on access to lines of credit from their overall group level debt facilities, or through leverage-style financing (where lenders are assessing the transaction based on expected revenues tested on an earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation or loan to value-style basis). These lenders may focus on a number of different revenue contracts that the data centre has, rather than on it having a revenue base underpinned by long-term lease/offtake arrangements with creditworthy counterparties.

Consistently with recent market trends affecting other asset classes (such as renewable energy), we are also seeing a rise in portfolio financing of data centres, as developers look to strengthen their financing terms by cross-collateralising a number of data centre assets. A lender's assessment of the portfolio will take into account a number of factors, including whether the assets are all operating or whether the portfolio includes any greenfield risk.

Internationally, the asset-backed securitisation market in the US experienced a resurgence in 2023, with $5.4 billion in securities backed by data centre revenues issued (and the first five months of 2024 saw issuances totalling $3.7 billion). While this trend has not yet reached Australian shores in a meaningful way in terms of data centre financing, we expect this market has potential to evolve as the asset class matures in Australia.